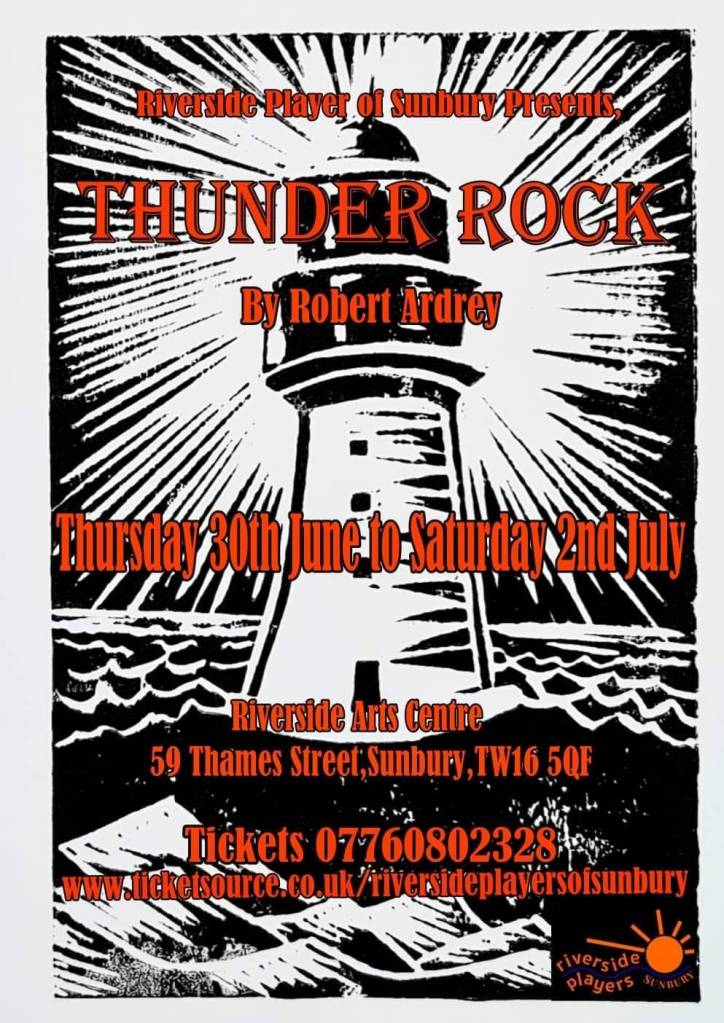

30th June – 2nd July 2022

Thunder Rock by Robert Ardrey is a play with a proud pedigree: a symbol of British resistance during World War II, it ran throughout the worsening Blitz in London and then on tour. With its message of hope, carpe diem, the futility of burying one’s head in the sand and the indomitable spirit of mankind, there is much that we can take from it during our own troubled times so it was good to see this curious, thought-provoking, period piece performed by the Riverside Players of Sunbury.

The action passes in a lighthouse on a tiny island in Lake Michigan where lighthouse keeper Charleston, disillusioned by life, has retreated from the world, receiving visitors just once a month when his pilot friend, Streeter, flies in supplies. In between, he conjures up for company the drowned passengers of a ship, wrecked on the island’s rocks 90 years before.

Marion Millinger and her cast more than did justice to this play. From the moment the audience entered the auditorium, those of us familiar with her style, knew we were attending a Marion Millinger production where the audience is, as she said in the programme, immersed in the action of the play. As we took our seats, we heard the sound of seagulls and waves lapping against the rocks and, unusually, the curtains were already drawn to show the whitewashed interior of the lighthouse with its rustic furniture and crates and an oar propped in one corner. We felt we were sitting in the lighthouse itself. The world of the characters is rarely confined to the stage in one of Marion’s productions, so coiled ropes and crates were propped on the auditorium floor, rocks abutted the forestage and the characters entered and exited through the coffee bar door, passing within a couple of feet of audience members in the front row. So far so apposite in a play with its message about the universal experience of mankind.

We got off to a lively start with Ron Millinger’s cantankerous Inspector Flanning, Peter Cornish’s lonely chancer, Streeter and Tom Fidler’s harried, hopeless Nonnie, panting, grumbling and stumbling as he unloaded Charleston’s supplies. I wasn’t sure I totally believed it when Cornish’s Streeter and Matt Markham’s Charleston squared up to each other, ending in Charleston swinging a punch, but the hard-drinking, tough-talking pattern of friendship between the two was otherwise well established and their slightly awkward hug as they parted – possibly for the last time – was moving. (I found myself wondering how Streeter could possibly fly a plane after the bottle of whisky he and Charleston briskly despatched! As we heard his plane leaving, I half expected to hear the sound of a screaming engine and a loud splash as he joined the 49ers at the bottom of Lake Michigan, taking Flanning and poor, longsuffering Nonnie with him.)

Matt Markham gave a commanding performance as Charleston – Matt excels at complicated, misanthropic characters and he captured well Charleston’s emotional journey from despair to renewed hope and the realisation that ‘to be alive is a privilege’. Having only previously seen Alan Saunders in panto, it was good to see him bring real gravitas to stern Captain Joshua, the only ‘ghost’ to be aware he is dead. In an impassioned speech, he persuades Charleston to see his passengers as they really were rather than as stereotypes. Each of these broken people from the past – ‘wandering fragments of a despairing time’ – carried their own heartache and we learned in turn why each of them had chosen to leave Europe to make a new life for themselves in America. It was at the point when Charleston loses control of the narrative that the other actors really came into their own. Chris Butler as the stately Dr Kurtz was finally allowed to speak and – in a flawless (to my ears, at least!) Austrian accent – argues the case for hope and optimism: ‘men may lose but mankind never.’ (Chris’s long wait to get to this ‘milestone’ play was amply rewarded by his well-observed performance.) Fiona Lawrie conveyed well the loneliness behind the tough exterior of the unmarried battle-hardened suffragette, Miss Kirby. Catriona Weatherley had less meaty material to work with as the doctor’s wife but was suitably lady-like and subservient, giving us a glimpse of incipient feminism when talking about women and childbirth. There were some moments of real pathos and I was particularly moved by the simple faith and optimism of Geoff Buckingham’s Briggs, despite all the knocks that life had delivered him and even after his beloved Millie has died giving birth to their tenth child. His ambition to make enough money in California to buy back his other five living children (given up for adoption) was heartbreaking, particularly as we knew he would never get there. Moving too was the doomed romance between Charleston and Carrie Millinger’s mournful, anxious Melanie, forever fretting about her father’s lost instruments. She brought a lump to my throat as she declared herself envious of the living and of all the girls Charleston might yet meet.

Overall, this play was very well cast, my one niggle being that the diction in one or two of the American accents could have been better. I didn’t always understand every word and I did wonder where in the world Captain Joshua came from. (However, I decided that a sea captain in 1849 may very well have spoken a different dialect from nowadays.)

Sound and lighting were used very effectively throughout this production, including the moving lighthouse beam and the scenes with the ghosts in low, blue-ish light giving way to the bright light of day when the ghosts have returned once more to their watery graves. Little touches like charleston music playing on the radio shortly before the character, Charleston, appears for the first time did not go unnoticed by the audience and Stephen Liddle’s radio announcer had all the intonations of an American broadcaster from that period. (Kurtz’s joy when he hears a Viennese Waltz on the radio was a moment of welcome humour.) Chantal Suppanee’s costumes were as ever appropriate for the period, creating a clear visual counterpoint between the passengers drowned in 1849 and Charleston et al in 1939. The ladies’ Victorian costumes were particularly good and showed real attention to detail, as did the props – the packet of Lucky Strikes, the aforementioned rustic crates and oar etc.

This might not have been a play known to many – and it was a pity more people did not come to see it – but it was a fascinating play that engendered lively discussion in the bar during the interval and stays in the mind long after you have left the auditorium. It is easy to see why it was such a hit in wartime London. Really well done to all concerned!

Vicki Prince

3rd July 2022

Leave a comment